|

|

| Volume No. 1 Issue No. 20 - Tuesday, April 30, 2002 |

My Journey to Kabul Afghanistan

by: Thomson Fontaine

A few days ago, I sat in the Kabul office of His Excellency Heydayat Amin Arsala (Vice Chairman of the Interim Administration of Afghanistan and the Minister of Finance), seeping authentic Afghan black tea and chewing nonchalantly on knookles and dried nuts. A few days ago, I sat in the Kabul office of His Excellency Heydayat Amin Arsala (Vice Chairman of the Interim Administration of Afghanistan and the Minister of Finance), seeping authentic Afghan black tea and chewing nonchalantly on knookles and dried nuts.

As I, along with three of my colleagues discussed with the Minister how we could best assist his country in its recovery efforts, I could not help but reflect on the notion of a failed state and feel deeply moved and sorry for a country so completely traumatized, torn apart and in a state of anguish after 23 years of war, neglect, and wanton destruction.

Earlier that day, I had worked my way past some anxious Tajik guards barricaded on the outer perimeter of the compound waving AK 47s, who appeared slightly unnerved by the presence of a well dressed �black� towing in the wake of two Europeans and a local interpreter.

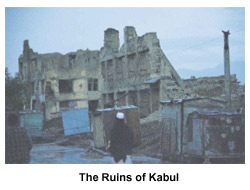

As we moved into what remained of the Finance Offices, I could not help but notice the bombed out remains of several large buses, their windshields blown off and riddled with bullet holes, lying abandoned in the far corner of the compound.

In fact all around the surrounding buildings and as far as the eye could see, was the telltale signs of damaged and unused buildings, all evidence of a violent past.

Working my way up dimly lit steps, I nodded in the direction of several persons in traditional Afghan garb who appeared to be everywhere present in the hallways and the stairs. My quick glances at the offices confirmed what I already knew. There were very few women present. Working my way up dimly lit steps, I nodded in the direction of several persons in traditional Afghan garb who appeared to be everywhere present in the hallways and the stairs. My quick glances at the offices confirmed what I already knew. There were very few women present.

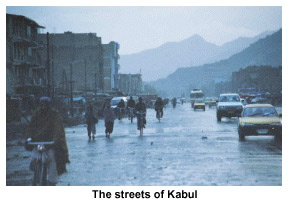

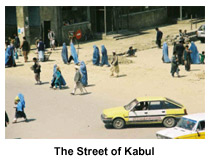

Six months after the ousting of the Taliban, women were still largely ignored. In fact, on the streets of Kabul, amidst the thousands of men sporting every conceivable type of military wear, and civilian garb, the occasional woman would be seen moving silently along, completely covered with the blue burkas introduced by the Taliban.

I marveled at the mind that could conceive of such a dress that succeeded so completely in reducing the women to a state of seeming nothingness.

Her burka ensured that she could neither be seen nor heard. Its sameness guaranteeing the loss of her identity, like a prisoner in a prison outfit, and many, fearing reprisals, and others still too deeply ashamed to act otherwise persist in wearing the burkas.

In one misguided moment, I stood transfixed, gazing intently at one such burka clad woman who happened to be within a few feet of me and headed in my direction. I was searching for her eyes as if this one look would reveal to me the pain, the isolation, the intense suffering that I was sure she was enduring.

Of course, I could not see her eyes as that too was covered by a stripped veil. As she approached, she did something that surprised me and revealed to me the carelessness of my action. She pulled the solid part of her burka across her eyes as if to forever cut off my searching stare and to completely cover whatever was left of her individuality, and also the shame that she must have felt.

My journey to Kabul started when I was asked if I would be interested in going to Afghanistan with three other colleagues to discuss the development of macroeconomics statistics with the Authorities, in light of the recovery efforts of that country.

Without even a second thought I said yes, eager to assist and play a role in helping rebuild the ravaged country, but also having this deep desire to be a witness to history unfolding.

It was only much later that I thought maybe I had made the wrong decision when, upon hearing of my impending trip, friends and family all voiced deep and repeated concerns for my safety.

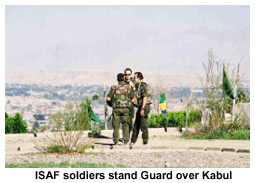

These deeply negative sentiments were somewhat reinforced by the continuing negative news coverage of armed gunmen on the loose in Kabul, of peacekeepers been shot at, of attempted coups and every other conceivable security concern. These deeply negative sentiments were somewhat reinforced by the continuing negative news coverage of armed gunmen on the loose in Kabul, of peacekeepers been shot at, of attempted coups and every other conceivable security concern.

This was further compounded when I heard of the living conditions under which I would have to survive for a couple of weeks. Undaunted, I continued with my preparation convinced that I was being given a unique opportunity to contribute to humanity and that save a direct threat on my life I would find my way to Kabul.

I have since confirmed that belief and feel a tremendous sense of pride and accomplishment in having made the trip.

A few days later, I boarded an airliner in a journey that would take me first to London, then across Iraqi airspace, through Abu Dhabi, and into Islamabad, Pakistan. After a welcome rest in that city, on a humid Sunday morning, I along with a number of journalists, army types, and UN personnel piled into a United Nations bus and headed for the airport. There, we boarded an airliner painted in the blue and white of the United Nations for the forty-minute flight to the Kabul airport.

My conversations with the lady seated on my right revealed that she worked for the US Army, and the lady from Paris on the left was on her way to Kabul to do a story on Afghan women for her magazine Marie Louise.

Throughout the short flight my mind raced with thoughts of what awaited me in Kabul. As the flight made its final approach into the airport, I peered expectantly out the window and gasped in breathless wonder as the buildings and landscape of Kabul took shape with the towering silhouette of the mountains standing guard.

Even at that vantage point, the extent of the damage to the city was evident. Scattered throughout the airport was the remains of tens of aircraft that had not survived the years of war. I stepped eagerly out of the plane and boarded a bus, which would probably not be so noticeable 35 years ago as it reeked and groaned the short two-minute ride to the terminal.

The terminal was a low building with its roof exposed, and electrical wire strewn haphazardly on the side of the building and where the ceiling should have been. Although it was about eleven in the morning, the building was dark and I could barely discern two men standing shoulder- to- shoulder behind a wooden stand dressed in military fatigues.

The one on my left was lean with a thin, graying beard, and the other was short, almost brutish in appearance�neither smiled nor looked up. They were completely focused on the passports that were pushed by passengers eager to be on their way. The one on my left was lean with a thin, graying beard, and the other was short, almost brutish in appearance�neither smiled nor looked up. They were completely focused on the passports that were pushed by passengers eager to be on their way.

Without looking up, the one with the gray beard handed me my passport after emphatically slamming a stamp with what appeared to be Afghanistan stenciled in green, right in the middle of the page.

Relieved, I moved ahead to claim my bags, and as I did so, two hands grabbed hold of it. I looked up quickly into the face of a man I consider to be in his mid thirties. His grin was warm and that told me he meant no harm.

I allowed him to carry my bags and followed quickly behind as he made his way outside. As I passed through the open door, an elderly gentleman dressed in a green uniform with a brightly colored insignia across his chest, cocked his head and stared quizzically at me.

His face only inches from mine, was wrinkled and there was a look of complete bewilderment in his eyes. I smiled nervously and moved on. I was to see that look over and over again during my stay. Outside, I pressed a couple of dollars into the hands of my bag carrier and with a quick smile he waved and disappeared into the crowd of dozens of young men assembled outside. Several of them started towards me. I was in Kabul.

The guesthouse was modest to say the least. Except for the beautiful Persian carpet, the room was bare. The cot on which I would have to sleep for the next several days was hard and slightly uncomfortable. At nights it was cold, so I was particularly thankful for the two thick blankets, made of wool and green in color that was provided.

The bathroom common to all the other guests was just down the hall. Over the next several days, devising ways of spending as little time as possible in there became a priority. At least at nights I went to sleep in the knowledge that just a few feet outside my door were armed soldiers standing guard. Fighters (mainly Tajik) from the Northern Alliance, they guarded government offices and buildings throughout Kabul.

On that first day in Kabul, I went with my colleagues to a restaurant. Our local guide graciously offered to order to which we graciously agreed given that the descriptions on the menu made no sense, at least to me.

I first stared in amazement then quickly diverted my eyes as the waiter with a loaded tray first plunked it on the floor and then proceeded to unload platters piled high with rice, chicken, beef, and kebabs of varying tastes. I quickly forgot about the tray on the floor as I concentrated on doing justice to what turned out to be a truly great meal.

Throughout my stay, mindful not to come across as been prudish, I never complained about the food. Before leaving Kabul however, I vowed on my return to the States to stay clear of rice and chicken for a long time since I am convinced that I consumed more than a years supply of these during my stay. It also did not help that I got sick from the food on more than one occasion.

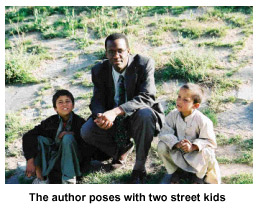

As we left the restaurant, nothing prepared me for what happened next. A kid barely older than 8, his face streaked with grime and dirt and nose running, extended his hand in our general direction, hoping for some change. As we left the restaurant, nothing prepared me for what happened next. A kid barely older than 8, his face streaked with grime and dirt and nose running, extended his hand in our general direction, hoping for some change.

Moved with pity, I was about to reach into my pocket for loose change when the Afghan guide immediately shouted that we should do no such thing. In a few seconds I would understand why.

As we made our way to the car, we were suddenly surrounded by a crowd of well over twenty men, women and children, pushing and shoving, all with hands extended, suddenly surrounded us.

We made it to the relative safety of the car, and even then I could hear the tapping on the car as the crowd of beggars peered imploringly in our direction. The car began to rock gently. I looked outside and saw women covered in the now familiar blue burkas with outstretched hands.

My heart felt like it was breaking to pieces within me. I was seized with despair. I wondered about humanity and the circumstances that would cause once proud, dignified people to be reduced to a faceless, begging mass of humanity.

Later, we were told that we should never give money since doing so would inevitably result in a riot. There would either be an immediate stampede to get to us, or there would be fighting to take whatever was given from the person fortunate enough to have received in the first place.

After about a week in Afghanistan, I felt rather safe and comfortable enough to walk the streets of Kabul. Truth is, I was tired of seeing everything and everyone in the safety of a car. I wanted to get to see the people, get a better feel for the place.

So, disregarding repeated security warnings that we should not walk the streets, one hot Saturday afternoon, I accepted an invitation from Mohammad, the assistant manager of the guesthouse to visit the downtown street bazaar.

After about three minutes of walking, I was assailed with self-doubt and wondered if I had not made a big mistake. As we made our way through the teeming mass of people, I could not help but notice that practically everyone was starring at me. Young men stopped in their tracks to stare, women in their burkas turned their heads in my direction, young children and older people in particular were more curious, and always there was this quizzical look.

Several people came up to me asking which country I came from. Mindful of the $50, 000 bounty on the head of Americans, I was quick to point out that I was from Africa. Two particular incidents stand out. The second more frightening than the first.

In the first instance, a young man in his twenties came up alongside me and in fluent English asked �what country are you from�, I quickly replied Africa, at which time he turned around and shouted something in Persian.

Alarmed, I spun around to see that a group of five other men had formed a tight circle around Mohammad and myself. It appeared however that I had given the right answer because as quickly as they appeared, they vanished into the crowd.

We were working our way back towards the safety of the guesthouse when a young soldier with a kalishnokov rifle slung carelessly over his shoulder approached us. I was immediately alarmed for two reasons.

Firstly, I had never before seen a soldier with a gun mingling freely in the crowd. In the past, armed soldiers were either guarding buildings or manning roadblocks. Secondly, he appeared to be very angry. He quickly grabbed Mohammad and started talking in a loud voice while pointing widely in my direction.

Although I could not understand, it was clear that he was extremely angry and agitated, and that I was the cause. As they continued talking, I could see the color drain from Mohammad�s face. Now completely panicked, I forced myself to relax and look unperturbed. In the meantime, a crowd had quickly gathered encircling the soldier and Mohammad.

With an eye on the soldier�s hand holding the gun, and using the crowd as some cover, I slowly started to back away. At one point, Mohammad turned to walk away and was abruptly shoved back by the soldier.

The conversation continued for another minute and then Mohammad was able to leave. I asked him what appeared to be the problem to which he replied that the soldier had asked him which country I came from and he replied that I was from the United States. The conversation continued for another minute and then Mohammad was able to leave. I asked him what appeared to be the problem to which he replied that the soldier had asked him which country I came from and he replied that I was from the United States.

That�s all he ever said and although I tried repeatedly to get him to reveal more, he never did. To this day, I wonder and worry about the intentions of the soldier. It was clear that he felt emboldened because he was armed.

What could he have been discussing with Mohammad in such a tone. I shiver to think of the possibilities. I had learned my lessons though. No more strolling the streets of Kabul, at least for now.

The story of Afghanistan is one of war, pain, suffering, the Taliban, and unimaginable poverty. It is also the story of first the British, then the Russians and now the Americans trying to impose their military will on a remarkably resilient people.

I wrestle to understand how people who appear so gentle and genuinely affectionate to each other could in an instant turn violently against each other. I visited the football stadium where only months before, men and women were dragged screaming to their deaths, executed on the penalty line to the roar of an approving crowd.

I saw the wanton destruction of buildings now standing in silent testimony to a violent past. I visited the jail where the Taliban tortured their opponents into submission. I saw the large number of men, women and children begging in the streets. I saw women reduced to a state of near nothingness. It is indeed a society deeply fractured.

It is also one of hope. The people are remarkably resilient. Determined to build their country from a past that is best forgotten.

They are anxious to learn, to embrace civility and build a modern society, free of the suffocating influence of communists, Taliban, and other extremist movements. I witnessed the thirst for knowledge first hand.

I was asked to give a seminar to a particular section of the Central Bank on issues of exchange rates, currency etc. I was told to expect about 12 persons. On the day of the seminar 35 staff members showed up.

An initial two-hour seminar was taught over five hours and delivered over two days. During the rule of the Taliban, many of the participants especially the women were sent home.

Others were denied access to learning. Data collection, economic analysis, in fact any activity not directly linked to learning the Koran and fighting the Northern Alliance was discouraged by the Taliban.

Some dreamed up ways of going around the system. Consider the story of �Latifah�. When I was first introduced to Latifah- a senior official at the Central Bank, I was immediately struck by her strength and appearance.

Tall and graceful, she wore make-up and her nails were colored and impeccably manicured. except for the thin veil that covered her head, she could be easily mistaken for a �western� woman.

During the Taliban rule, she was dismissed from her position but did not allow that to deter her. She started a secret organization that provided training in computers and English for girls who were denied schooling under the Taliban. Hers is a remarkable story of resilience and of the human spirit. Of good triumphing over evil.

Javed my 18-year-old interpreter who has dreams of becoming a medical doctor recounted how he was arrested by the Taliban and forced to shave his hair because he was told it was too long. Javed my 18-year-old interpreter who has dreams of becoming a medical doctor recounted how he was arrested by the Taliban and forced to shave his hair because he was told it was too long.

In the end, he fled with his family like thousands of other families to Peshawar, Pakistan where he remained until the collapse of the Taliban. Now he was playing his part in assisting in his country�s development until he could go overseas to become a doctor like his father before him. The United Nations estimates that in three months over 800, 000 Afghans had returned from Pakistan, and the trend continues.

As I rose to shake hands with his Excellency, I could not help but say a prayer for the country. In a strange way, I feel drawn to this land. I promised him that I would return to complete what I started. I have already started making plans, this time for the month of July.

|

|

|

|